Social Justice Shirts Make Science Great Again

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges inside a society.[i] In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals fulfill their societal roles and receive what was their due from order.[2] [3] [four] In the current movements for social justice, the emphasis has been on the breaking of barriers for social mobility, the cosmos of safe nets, and economical justice.[5] [6] [seven] [9] [ excessive citations ] Social justice assigns rights and duties in the institutions of club, which enables people to receive the bones benefits and burdens of cooperation. The relevant institutions oft include taxation, social insurance, public health, public school, public services, labor law and regulation of markets, to ensure distribution of wealth, and equal opportunity.[10]

Interpretations that relate justice to a reciprocal relationship to society are mediated past differences in cultural traditions, some of which emphasize the private responsibility toward society and others the equilibrium between access to power and its responsible employ.[11] Hence, social justice is invoked today while reinterpreting historical figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas, in philosophical debates about differences amidst human beings, in efforts for gender, ethnic, and social equality, for advocating justice for migrants, prisoners, the environment, and the physically and developmentally disabled.[12] [13] [14]

While concepts of social justice tin can be found in classical and Christian philosophical sources, from Plato and Aristotle to Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas, the term social justice finds its primeval uses in the belatedly 18th century, albeit with unclear theoretical or practical meanings.[xv] [16] [17] The use of the term was early on discipline to accusations of redundancy and of rhetorical flourish, perhaps but not necessarily related to amplifying one view of distributive justice.[xviii] In the coining and definition of the term in the natural law social scientific treatise of Luigi Taparelli, in the early 1840s,[19] Taparelli established the natural police force principle that corresponded to the evangelical principle of brotherly beloved—i.e. social justice reflects the duty one has to one'southward other self in the interdependent abstract unity of the human person in club.[20] After the Revolutions of 1848 the term was popularized generically through the writings of Antonio Rosmini-Serbati.[21] [22]

In the late industrial revolution, Progressive Era American legal scholars began to use the term more than, particularly Louis Brandeis and Roscoe Pound. From the early 20th century it was too embedded in international constabulary and institutions; the preamble to found the International Labour Organization recalled that "universal and lasting peace tin can exist established just if it is based upon social justice." In the afterward 20th century, social justice was made central to the philosophy of the social contract, primarily by John Rawls in A Theory of Justice (1971). In 1993, the Vienna Declaration and Plan of Activity treats social justice as a purpose of homo rights education.[23] [24]

History [edit]

An artist's rendering of what Plato might accept looked like. From Raphael's early 16th century painting "Scuola di Atene".

The different concepts of justice, as discussed in ancient Western philosophy, were typically centered upon the community.

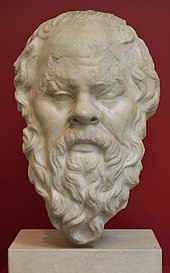

Roman copy in marble of a Greek bronze bust of Aristotle past Lysippos, c. 330 BC. The alabaster mantle is modern.

- Plato wrote in The Republic that it would exist an ideal state that "every member of the community must be assigned to the form for which he finds himself best fitted."[25] In an article for J.N.V University, author D.R. Bhandari says, "Justice is, for Plato, at once a part of man virtue and the bond, which joins man together in lodge. Information technology is the identical quality that makes good and social. Justice is an order and duty of the parts of the soul, it is to the soul as health is to the trunk. Plato says that justice is not mere forcefulness, but it is a harmonious strength. Justice is not the right of the stronger simply the effective harmony of the whole. All moral conceptions circumduct about the expert of the whole-individual besides as social".[26]

- Plato believed rights existed only betwixt costless people, and the law should take "account in the first case of relations of inequality in which individuals are treated in proportion to their worth and only secondarily of relations of equality." Reflecting this fourth dimension when slavery and subjugation of women was typical, ancient views of justice tended to reflect the rigid form systems that still prevailed. On the other hand, for the privileged groups, strong concepts of fairness and the community existed. Distributive justice was said by Aristotle to require that people were distributed appurtenances and assets co-ordinate to their merit.[27]

- Socrates (through Plato's dialogue Crito) is credited with developing the thought of a social contract, whereby people ought to follow the rules of a society, and accept its burdens because they have accepted its benefits.[28] During the Heart Ages, religious scholars particularly, such as Thomas Aquinas continued discussion of justice in various means, but ultimately connected being a good citizen to the purpose of serving God.

Afterward the Renaissance and Reformation, the mod concept of social justice, as developing human potential, began to emerge through the work of a series of authors. Baruch Spinoza in On the Improvement of the Understanding (1677) contended that the one true aim of life should be to acquire "a human character much more stable than [ane's] own", and to accomplish this "pitch of perfection... The principal practiced is that he should get in, together with other individuals if possible, at the possession of the aforesaid character."[29] During the enlightenment and responding to the French and American Revolutions, Thomas Paine similarly wrote in The Rights of Man (1792) society should give "genius a fair and universal take chances" and so "the structure of authorities ought to be such as to bring frontwards... all that extent of capacity which never fails to appear in revolutions."[30]

Social justice has been traditionally credited to be coined by Jesuit priest Luigi Taparelli in the 1840s, but the expression is older

Although there is no certainty almost the first use of the term "social justice", early on sources tin can be constitute in Europe in the 18th century.[31] Some references to the use of the expression are in articles of journals aligned with the spirit of the Enlightenment, in which social justice is described equally an obligation of the monarch;[32] [33] also the term is present in books written by Cosmic Italian theologians, notably members of the Lodge of Jesus.[34] Thus, according to this sources and the context, social justice was another term for "the justice of guild", the justice that rules the relations among individuals in society, without whatever mention to socio-economic equity or man dignity.[31]

The usage of the term started to go more than frequent by Catholic thinkers from the 1840s, beginning with the Jesuit Luigi Taparelli in Civiltà Cattolica, and based on the work of St. Thomas Aquinas. Taparelli argued that rival capitalist and socialist theories, based on subjective Cartesian thinking, undermined the unity of society present in Thomistic metaphysics as neither were sufficiently concerned with ethics.[eighteen] Writing in 1861, the influential British philosopher and economist, John Stuart Mill stated in Utilitarianism his view that "Society should treat all equally well who have deserved equally well of it, that is, who accept deserved equally well admittedly. This is the highest abstract standard of social and distributive justice; towards which all institutions, and the efforts of all virtuous citizens, should be made in the utmost degree to converge."[35]

In the afterwards 19th and early on 20th century, social justice became an of import theme in American political and legal philosophy, particularly in the work of John Dewey, Roscoe Pound and Louis Brandeis. One of the prime number concerns was the Lochner era decisions of the U.s. Supreme Court to strike down legislation passed by state governments and the Federal regime for social and economic comeback, such equally the viii-hour day or the right to join a trade union. After the First World State of war, the founding document of the International Labour Organization took up the same terminology in its preamble, stating that "peace can exist established just if it is based on social justice". From this bespeak, the discussion of social justice entered into mainstream legal and academic discourse.

In 1931, the Pope Pius XI explicitly referred to the expression, forth with the concept of subsidiarity, for the kickoff time in Catholic social teaching in the encyclical Quadragesimo anno. Then again in Divini Redemptoris, the church building pointed out that the realization of social justice relied on the promotion of the dignity of human person.[36] During the 1930s, the term was widely associated with pro-Nazi and antisemitic groups, such as the Christian Front.[37] Social Justice was the slogan of Charles Coughlin, and the name of his newspaper. Because of the documented influence of Divini Redemptoris in its drafters,[38] the Constitution of Republic of ireland was the first one to plant the term equally a principle of the economy in the State, and then other countries effectually the world did the same throughout the 20th century, even in socialist regimes such as the Cuban Constitution in 1976.[31]

In the late 20th century, several liberal and bourgeois thinkers, notably Friedrich Hayek rejected the concept by stating that information technology did non hateful anything, or meant besides many things.[39] However the concept remained highly influential, particularly with its promotion by philosophers such as John Rawls. Even though the meaning of social justice varies, at least three mutual elements can be identified in the contemporary theories about information technology: a duty of the State to distribute certain vital ways (such as economic, social, and cultural rights), the protection of human nobility, and affirmative actions to promote equal opportunities for everybody.[31]

Contemporary theory [edit]

Philosophical perspectives [edit]

Cosmic values [edit]

Hunter Lewis' piece of work promoting natural healthcare and sustainable economies advocates for conservation as a key premise in social justice. His manifesto on sustainability ties the continued thriving of human life to existent conditions, the environment supporting that life, and associates injustice with the detrimental effects of unintended consequences of man actions. Quoting classical Greek thinkers like Epicurus on the proficient of pursuing happiness, Hunter also cites ornithologist, naturalist, and philosopher Alexander Skutch in his volume Moral Foundations:

The common feature which unites the activities most consistently forbidden by the moral codes of civilized peoples is that past their very nature they cannot be both habitual and enduring, because they tend to destroy the conditions which make them possible.[40]

Pope Bridegroom Sixteen cites Teilhard de Chardin in a vision of the cosmos as a 'living host'[41] embracing an understanding of ecology that includes humanity'due south relationship to others, that pollution affects non just the natural world but interpersonal relations as well. Cosmic harmony, justice and peace are closely interrelated:

If you want to cultivate peace, protect creation.[42]

In The Quest for Catholic Justice, Thomas Sowell writes that seeking utopia, while admirable, may have disastrous effects if washed without strong consideration of the economical underpinnings that support gimmicky society.[43]

John Rawls [edit]

Political philosopher John Rawls draws on the utilitarian insights of Bentham and Mill, the social contract ideas of John Locke, and the chiselled imperative ideas of Kant. His start statement of principle was made in A Theory of Justice where he proposed that, "Each person possesses an inviolability founded on justice that fifty-fifty the welfare of society every bit a whole cannot override. For this reason justice denies that the loss of freedom for some is made right past a greater skillful shared by others."[44] A deontological proposition that echoes Kant in framing the moral adept of justice in absolutist terms. His views are definitively restated in Political Liberalism where society is seen "as a fair organisation of co-operation over time, from one generation to the adjacent".[45]

All societies have a basic structure of social, economic, and political institutions, both formal and breezy. In testing how well these elements fit and work together, Rawls based a key test of legitimacy on the theories of social contract. To decide whether any particular system of collectively enforced social arrangements is legitimate, he argued that one must expect for agreement by the people who are subject to it, but not necessarily to an objective notion of justice based on coherent ideological grounding. Obviously, not every citizen can be asked to participate in a poll to make up one's mind his or her consent to every proposal in which some degree of coercion is involved, so 1 has to assume that all citizens are reasonable. Rawls constructed an argument for a 2-stage process to make up one's mind a citizen'southward hypothetical understanding:

- The citizen agrees to exist represented by Ten for certain purposes, and, to that extent, Ten holds these powers as a trustee for the citizen.

- X agrees that enforcement in a particular social context is legitimate. The citizen, therefore, is spring by this conclusion because information technology is the function of the trustee to stand for the citizen in this manner.

This applies to one person who represents a small group (e.g., the organiser of a social upshot setting a apparel code) as every bit as it does to national governments, which are ultimate trustees, holding representative powers for the benefit of all citizens within their territorial boundaries. Governments that fail to provide for welfare of their citizens according to the principles of justice are not legitimate. To emphasise the full general principle that justice should rising from the people and not be dictated by the police-making powers of governments, Rawls asserted that, "There is ... a full general presumption against imposing legal and other restrictions on acquit without sufficient reason. But this presumption creates no special priority for any particular liberty."[46] This is support for an unranked gear up of liberties that reasonable citizens in all states should respect and uphold — to some extent, the list proposed past Rawls matches the normative human rights that have international recognition and directly enforcement in some nation states where the citizens need encouragement to act in a way that fixes a greater degree of equality of outcome. According to Rawls, the basic liberties that every good society should guarantee are:

- Liberty of thought;

- Liberty of conscience every bit it affects social relationships on the grounds of religion, philosophy, and morality;

- Political liberties (e.g., representative democratic institutions, freedom of spoken communication and the press, and freedom of assembly);

- Freedom of association;

- Freedoms necessary for the liberty and integrity of the person (namely: freedom from slavery, freedom of move and a reasonable degree of freedom to choose one'southward occupation); and

- Rights and liberties covered by the rule of law.

Thomas Pogge [edit]

Thomas Pogge'due south arguments pertain to a standard of social justice that creates human rights deficits. He assigns responsibility to those who actively cooperate in designing or imposing the social institution, that the guild is foreseeable as harming the global poor and is reasonably avoidable. Pogge argues that social institutions accept a negative duty to non harm the poor.[47] [48]

Pogge speaks of "institutional cosmopolitanism" and assigns responsibility to institutional schemes[49] for deficits of human rights. An case given is slavery and third parties. A tertiary party should non recognize or enforce slavery. The institutional guild should exist held responsible only for deprivations of human rights that it establishes or authorizes. The current institutional design, he says, systematically harms developing economies past enabling corporate tax evasion,[50] illicit fiscal flows, corruption, trafficking of people and weapons. Joshua Cohen disputes his claims based on the fact that some poor countries have done well with the current institutional design.[51] Elizabeth Kahn argues that some of these responsibilities[ vague ] should utilize globally.[52]

United nations [edit]

The United nations calls social justice "an underlying principle for peaceful and prosperous coexistence within and among nations.[53]

The United nations' 2006 document Social Justice in an Open World: The Role of the Un, states that "Social justice may be broadly understood as the fair and empathetic distribution of the fruits of economical growth..."[54] : xvi

The term "social justice" was seen by the U.N. "as a substitute for the protection of man rights [and] start appeared in United Nations texts during the second half of the 1960s. At the initiative of the Soviet Union, and with the support of developing countries, the term was used in the Declaration on Social Progress and Development, adopted in 1969."[54] : 52

The aforementioned document reports, "From the comprehensive global perspective shaped by the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Homo Rights, fail of the pursuit of social justice in all its dimensions translates into de facto acceptance of a future marred past violence, repression and chaos."[54] : 6 The report concludes, "Social justice is not possible without strong and coherent redistributive policies conceived and implemented by public agencies."[54] : 16

The aforementioned United nations document offers a curtailed history: "[T]he notion of social justice is relatively new. None of history's keen philosophers—not Plato or Aristotle, or Confucius or Averroes, or even Rousseau or Kant—saw the need to consider justice or the redress of injustices from a social perspective. The concept first surfaced in Western thought and political language in the wake of the industrial revolution and the parallel evolution of the socialist doctrine. It emerged as an expression of protestation confronting what was perceived every bit the backer exploitation of labor and every bit a focal point for the development of measures to improve the human condition. It was born as a revolutionary slogan embodying the ideals of progress and fraternity. Following the revolutions that shook Europe in the mid-1800s, social justice became a rallying cry for progressive thinkers and political activists.... By the mid-twentieth century, the concept of social justice had become central to the ideologies and programs of near all the leftist and centrist political parties around the world..."[54] : xi–12

Another fundamental area of homo rights and social justice is the Un's defense of children's rights worldwide. In 1989, the Convention on the Rights of the Child was adopted and available for signature, ratification and accession by General Associates resolution 44/25.[55] According to OHCHR, this convention entered into force on two September 1990. This convention upholds that all states have the obligation to "protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent handling, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse."[55]

Religious perspectives [edit]

Abrahamic religions [edit]

Christianity [edit]

Evangelicalism [edit]

Time mag noted that younger Evangelicals besides increasingly appoint in social justice.[56] John Stott traced the call for social justice back to the cross, "The cantankerous is a revelation of God'south justice also as of his love. That is why the community of the cantankerous should concern itself with social justice also as with loving philanthropy."[57]

Methodism [edit]

From its founding, Methodism was a Christian social justice movement. Nether John Wesley's management, Methodists became leaders in many social justice issues of the solar day, including the prison reform and abolition movements. Wesley himself was amidst the first to preach for slaves rights attracting significant opposition.[58] [59] [lx]

Today, social justice plays a major part in the United Methodist Church building and the Free Methodist Church building.[61] The Book of Discipline of the United Methodist Church says, "We concord governments responsible for the protection of the rights of the people to gratuitous and fair elections and to the freedoms of speech, religion, associates, communications media, and petition for redress of grievances without fright of reprisal; to the right to privacy; and to the guarantee of the rights to acceptable food, clothing, shelter, instruction, and health care."[62] The United Methodist Church likewise teaches population control as part of its doctrine.[63]

Catholicism [edit]

Catholic social teaching consists of those aspects of Roman Catholic doctrine which relate to matters dealing with the respect of the individual human life. A distinctive feature of Cosmic social doctrine is its concern for the poorest and virtually vulnerable members of society. Ii of the seven key areas[64] of "Catholic social didactics" are pertinent to social justice:

- Life and nobility of the human person: The foundational principle of all Catholic social educational activity is the sanctity of all man life and the inherent nobility of every human being person, from conception to natural death. Human life must be valued above all material possessions.

- Preferential option for the poor and vulnerable: Catholics believe Jesus taught that on the Day of Judgement God volition ask what each person did to help the poor and needy: "Amen, I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me."[65] The Catholic Church building believes that through words, prayers and deeds one must show solidarity with, and compassion for, the poor. The moral exam of any society is "how it treats its almost vulnerable members. The poor accept the well-nigh urgent moral claim on the conscience of the nation. People are called to wait at public policy decisions in terms of how they affect the poor."[66]

Modern Catholic social instruction is ofttimes thought to have begun with the encyclicals of Pope Leo 13.[18]

- Pope Leo XIII, who studied nether Taparelli, published in 1891 the encyclical Rerum novarum (On the Condition of the Working Classes; lit. "On new things"), rejecting both socialism and capitalism, while defending labor unions and private property. He stated that society should be based on cooperation and not class conflict and competition. In this document, Leo set up out the Catholic Church'south response to the social instability and labor conflict that had arisen in the wake of industrialization and had led to the ascent of socialism. The Pope advocated that the role of the state was to promote social justice through the protection of rights, while the church must speak out on social issues to teach correct social principles and ensure class harmony.

- The encyclical Quadragesimo anno (On Reconstruction of the Social Order, literally "in the fortieth yr") of 1931 by Pope Pius XI, encourages a living wage,[67] subsidiarity, and advocates that social justice is a personal virtue also equally an attribute of the social lodge, saying that society can be merely but if individuals and institutions are just.

- Pope John Paul II added much to the corpus of the Catholic social teaching, penning three encyclicals which focus on problems such every bit economics, politics, geo-political situations, buying of the means of product, private property and the "social mortgage", and private property. The encyclicals Laborem exercens, Sollicitudo rei socialis, and Centesimus annus are but a minor portion of his overall contribution to Catholic social justice. Pope John Paul II was a stiff advocate of justice and man rights, and spoke forcefully for the poor. He addresses issues such as the problems that technology can nowadays should it exist misused, and admits a fearfulness that the "progress" of the globe is not true progress at all, if it should denigrate the value of the human person. He argued in Centesimus annus that private property, markets, and honest labor were the keys to alleviating the miseries of the poor and to enabling a life that can limited the fullness of the human person.

- Pope Benedict Sixteen'southward encyclical Deus caritas est ("God is Love") of 2006 claims that justice is the defining business organisation of the state and the key business organization of politics, and non of the church, which has charity as its central social business organization. It said that the laity has the specific responsibility of pursuing social justice in civil gild and that the church'south active function in social justice should exist to inform the debate, using reason and natural law, and too past providing moral and spiritual formation for those involved in politics.

- The official Catholic doctrine on social justice can be found in the volume Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, published in 2004 and updated in 2006, by the Pontifical Council Iustitia et Pax.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church building (§§ 1928–1948) contains more detail of the church's view of social justice.[68]

Islam [edit]

In Muslim history, Islamic governance has frequently been associated with social justice.[ additional citation(south) needed ] Establishment of social justice was one of the motivating factors of the Abbasid revolt confronting the Umayyads.[69] The Shi'a believe that the return of the Mahdi will herald in "the messianic historic period of justice" and the Mahdi along with the Isa (Jesus) will stop plunder, torture, oppression and discrimination.[seventy]

For the Muslim Brotherhood the implementation of social justice would require the rejection of consumerism and communism. The Brotherhood strongly affirmed the right to individual belongings as well as differences in personal wealth due to factors such every bit hard work. However, the Brotherhood held Muslims had an obligation to assist those Muslims in demand. It held that zakat (alms-giving) was not voluntary charity, but rather the poor had the right to assistance from the more than fortunate.[71] Most Islamic governments therefore enforce the zakat through taxes.

Judaism [edit]

In To Heal a Fractured Globe: The Ideals of Responsibility, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks states that social justice has a fundamental place in Judaism. One of Judaism's almost distinctive and challenging ideas is its ethics of responsibility reflected in the concepts of simcha ("gladness" or "joy"), tzedakah ("the religious obligation to perform charity and philanthropic acts"), chesed ("deeds of kindness"), and tikkun olam ("repairing the world").[72]

Eastern religions [edit]

Hinduism [edit]

The present-day Jāti hierarchy is undergoing changes for a variety of reasons including 'social justice', which is a politically popular opinion in autonomous India. Institutionalized affirmative activity has promoted this. The disparity and wide inequalities in social behaviour of the jātis – sectional, endogamous communities centred on traditional occupations – has led to various reform movements in Hinduism. While legally outlawed, the degree organization remains strong in practice.[73]

Traditional Chinese religion [edit]

The Chinese concept of Tian Ming has occasionally been perceived[ past whom? ] as an expression of social justice.[74] Through information technology, the deposition of unfair rulers is justified in that civic dissatisfaction and economical disasters is perceived as Sky withdrawing its favor from the Emperor. A successful rebellion is considered definite proof that the Emperor is unfit to rule.

[edit]

Social justice is also a concept that is used to describe the motility towards a socially but world, east.g., the Global Justice Motion. In this context, social justice is based on the concepts of human rights and equality, and tin be defined equally "the mode in which human being rights are manifested in the everyday lives of people at every level of society".[75]

Several movements are working to achieve social justice in society. These movements are working toward the realization of a globe where all members of a society, regardless of background or procedural justice, have bones human being rights and equal admission to the benefits of their society.[76]

Liberation theology [edit]

Liberation theology[77] is a move in Christian theology which conveys the teachings of Jesus Christ in terms of a liberation from unjust economic, political, or social weather. Information technology has been described past proponents as "an estimation of Christian faith through the poor'south suffering, their struggle and promise, and a critique of society and the Cosmic faith and Christianity through the optics of the poor",[78] and past detractors equally Christianity perverted by Marxism and Communism.[79]

Although liberation theology has grown into an international and inter-denominational movement, it began as a motion within the Catholic Church in Latin America in the 1950s–1960s. Information technology arose principally as a moral reaction to the poverty caused by social injustice in that region.[80] It achieved prominence in the 1970s and 1980s. The term was coined by the Peruvian priest, Gustavo Gutiérrez, who wrote one of the movement's most famous books, A Theology of Liberation (1971). Co-ordinate to Sarah Kleeb, "Marx would surely take consequence," she writes, "with the appropriation of his works in a religious context...at that place is no way to reconcile Marx'south views of religion with those of Gutierrez, they are just incompatible. Despite this, in terms of their understanding of the necessity of a just and righteous world, and the nearly inevitable obstructions along such a path, the 2 take much in mutual; and, particularly in the first edition of [A Theology of Liberation], the use of Marxian theory is quite axiomatic."[81]

Other noted exponents are Leonardo Boff of Brazil, Carlos Mugica of Argentina, Jon Sobrino of Republic of el salvador, and Juan Luis Segundo of Uruguay.[82] [83]

Wellness care [edit]

Social justice has more recently made its style into the field of bioethics. Discussion involves topics such every bit affordable access to health intendance, peculiarly for low income households and families. The discussion as well raises questions such as whether gild should bear healthcare costs for depression income families, and whether the global marketplace is the all-time way to distribute healthcare. Ruth Faden of the Johns Hopkins Berman Establish of Bioethics and Madison Powers of Georgetown University focus their assay of social justice on which inequalities matter the most. They develop a social justice theory that answers some of these questions in concrete settings.

Social injustices occur when there is a preventable departure in health states among a population of people. These social injustices take the course of health inequities when negative health states such as malnourishment, and infectious diseases are more prevalent in impoverished nations.[84] These negative health states can often exist prevented by providing social and economic structures such as primary healthcare which ensures the general population has equal access to health care services regardless of income level, gender, education or whatsoever other stratifying factors. Integrating social justice with health inherently reflects the social determinants of health model without discounting the role of the bio-medical model.[85]

Health inequalities [edit]

The sources of health inequalities are rooted in injustices associated with racism, sexual activity discrimination, and social class. Richard Hofrichter and his colleagues examine the political implications of various perspectives used to explicate health inequities and explore alternative strategies for eliminating them.[86]

Human rights education [edit]

The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Activeness affirm that "Human rights educational activity should include peace, democracy, development and social justice, as prepare forth in international and regional human rights instruments, to achieve mutual agreement and awareness to strengthen universal commitment to homo rights."[87]

Ecology and surroundings [edit]

Social justice principles are embedded in the larger environmental movement. The third principle of the World Charter is social and economic justice, which is described as seeking to eradicate poverty every bit an ethical, social, and environmental imperative, ensure that economic activities and institutions at all levels promote human development in an equitable and sustainable manner, assert gender equality and disinterestedness as prerequisites to sustainable development and ensure universal access to education, health care, and economic opportunity, and uphold the right of all, without bigotry, to a natural and social environs supportive of human nobility, actual health, and spiritual well-existence, with special attention to the rights of ethnic peoples and minorities.

The climate justice and ecology justice movements likewise contain social justice principles, ideas, and practices. Climate justice and ecology justice, every bit movements within the larger ecological and environmental movement, each incorporate social justice in a item way. Climate justice includes business organisation for social justice pertaining to greenhouse gas emissions,[88] climate-induced environmental displacement,[89] besides as climate change mitigation and accommodation. Environmental justice includes concern for social justice pertaining to either ecology benefits[90] or environmental pollution[91] based on their equitable distribution across communities of color, communities of various socio and economic stratification, or any other barriers to justice.

Criticism [edit]

Michael Novak argues that social justice has seldom been fairly divers, arguing:

[Due west]hole books and treatises have been written about social justice without e'er defining it. It is immune to float in the air as if everyone will recognize an case of it when it appears. This vagueness seems indispensable. The minute ane begins to ascertain social justice, 1 runs into embarrassing intellectual difficulties. It becomes, about oft, a term of art whose operational meaning is, "Nosotros need a law against that." In other words, it becomes an musical instrument of ideological intimidation, for the purpose of gaining the ability of legal coercion.[92]

Friedrich Hayek of the Austrian School of economics rejected the very idea of social justice as meaningless, cocky-contradictory, and ideological, believing that to realize any degree of social justice is unfeasible, and that the attempt to do and so must destroy all freedom:

In that location can be no test by which we tin can detect what is 'socially unjust' because at that place is no subject past which such an injustice can be committed, and there are no rules of individual conduct the observance of which in the market society would secure to the individuals and groups the position which as such (as distinguished from the process past which it is determined) would announced just to united states. [Social justice] does non vest to the category of fault simply to that of nonsense, like the term 'a moral rock'.[93]

Hayek argued that proponents of social justice often nowadays information technology every bit a moral virtue only most of their descriptions pertain to impersonal states of affairs (e.g. income inequality, poverty), which are cited equally "social injustice." Hayek argued that social justice is either a virtue or it is not. If it is, it tin can merely be ascribed to the actions of individuals. However, most who use the term ascribe it to social systems, so "social justice" in fact describes a regulative principle of order; they are interested not in virtue but power.[92] For Hayek, this notion of social justices presupposes that people are guided by specific external directions rather than internal, personal rules of just behave. It farther presupposes that one can never be held accountable for ones own behaviour, equally this would exist "blaming the victim." Co-ordinate to Hayek, the function of social justice is to blame someone else, often attributed to "the arrangement" or those who are supposed, mythically, to command it. Thus it is based on the appealing idea of "you suffer; your suffering is acquired by powerful others; these oppressors must exist destroyed."[92]

Ben O'Neill of the University of New S Wales and the Mises Constitute argues:

[For advocates of "social justice"] the notion of "rights" is a mere term of entitlement, indicative of a claim for any possible desirable skillful, no matter how important or trivial, abstract or tangible, recent or ancient. It is but an exclamation of desire, and a declaration of intention to use the language of rights to acquire said desire. In fact, since the program of social justice inevitably involves claims for authorities provision of goods, paid for through the efforts of others, the term actually refers to an intention to use force to acquire i's desires. Not to earn desirable goods by rational thought and action, product and voluntary substitution, but to get in there and forcibly take goods from those who can supply them![94]

Run into as well [edit]

- Activism

- "Across Vietnam: A Time to Pause Silence", i of many pro–social justice speeches delivered past Martin Luther King Jr.

- Choosing the Common Practiced

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Economic justice

- Teaching for Justice

- Environmental racism

- Essentially contested concept

- Global justice

- Labour police force and labour rights

- Left-wing politics

- Resource justice

- Right to education

- Right to health

- Right to housing

- Right to social security

- Social justice art

- Social justice warrior

- Social law

- Social work

- Solidarity

- National Union for Social Justice (organization)

- World Day of Social Justice

- All pages with titles beginning with Social justice

- All pages with titles containing Social justice

References [edit]

- ^ "social justice". Oxford languages . Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Aristotle, The Politics (ca 350 BC)

- ^ Clark, Mary T. (2015). "Augustine on Justice," a Chapter in Augustine and Social Justice. Lexington Books. pp. iii–10. ISBN978-1-4985-0918-3.

- ^ Banai, Ayelet; Ronzoni, Miriam; Schemmel, Christian (2011). Social Justice, Global Dynamics : Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Florence: Taylor and Francis. ISBN978-0-203-81929-6.

- ^ Kitching, G. N. (2001). Seeking Social Justice Through Globalization Escaping a Nationalist Perspective. Academy Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. three–10. ISBN978-0-271-02377-9.

- ^ Hillman, Arye L. (2008). "Globalization and Social Justice". The Singapore Economic Review. 53 (2): 173–189. doi:10.1142/s0217590808002896.

- ^ Lawrence, Cecile & Natalie Churn (2012). Movements in Time Revolution, Social Justice, and Times of Alter. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Pub. pp. xi–15. ISBN978-1-4438-4552-vi.

- ^ El Khoury, Ann (2015). Globalization Development and Social Justice : A propositional political approach. Florence: Taylor and Francis. pp. 1–20. ISBN978-i-317-50480-1.

- ^ John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (1971) four, "the principles of social justice: they provide a way of assigning rights and duties in the bones institutions of society and they define the appropriate distribution of benefits and burdens of social co-operation."

- ^ Aiqing Zhang; Feifei Xia; Chengwei Li (2007). "The Antecedents of Assistance Giving in Chinese Culture: Attribution, Judgment of Responsibility, Expectation Change and the Reaction of Affect". Social Behavior and Personality. 35 (ane): 135–142. doi:ten.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.135.

- ^ Smith, Justin E. H. (2015). Nature, Man Nature, and Human Difference : Race in Early Modern Philosophy. Princeton University Press. p. 17. ISBN978-1-4008-6631-1.

- ^ Trương, Thanh-Đạm (2013). Migration, Gender and Social Justice: Perspectives on Human Insecurity. Springer. pp. 3–26. ISBN978-3-642-28012-2.

- ^ Teklu, Abebe Abay (2010). "We Cannot Handclapping with 1 Paw: Global Socio–Political Differences in Social Support for People with Visual Impairment". International Journal of Ethiopian Studies. five (i): 93–105.

- ^ J. Zajda, Due south. Majhanovich, Five. Rust, Instruction and Social Justice, 2006, ISBN 1-4020-4721-v

- ^ Clark, Mary T. (2015). "Augustine on Justice," a Chapter in Augustine and Social Justice. Lexington Books. pp. 3–x. ISBN978-ane-4985-0918-3.

- ^ Paine, Thomas. Agrestal Justice. Printed by R. Folwell, for Benjamin Franklin Bache.

- ^ a b c Behr, Thomas. Social Justice and Subsidiarity: Luigi Taparelli and the Origins of Mod Catholic Social Idea (Washington DC: Cosmic Academy of American Press, December 2019).

- ^ Luigi Taparelli, SJ, Saggio teoretico di dritto naturale appogiato sul fatto (Palermo: Antonio Muratori, 1840-43), Sections 341-364.

- ^ Behr, Thomas. Social Justice and Subsidiarity: Luigi Taparelli and the Origins of Modern Cosmic Social Thought(Washington DC: Catholic Academy of American Press, December 2019), pp. 149-154.

- ^ Rosmini-Serbati, The Constitution under Social Justice. trans. A. Mingardi (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2007).

- ^ Pérez-Garzón, Carlos Andrés (14 January 2018). "Unveiling the Meaning of Social Justice in Colombia". Mexican Law Review. 10 (ii): 27–66. ISSN 2448-5306. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ The Preamble of ILO Constitution

- ^ Vienna Announcement and Programme of Action, Part II, D.

- ^ Plato, The Commonwealth (ca 380BC)

- ^ "20th WCP: Plato's Concept of Justice: An Analysis". Archived from the original on five October 2016.

- ^ Nicomachean Ideals V.3

- ^ Plato, Crito (ca 380 BC)

- ^ B Spinoza, On the Improvement of the Understanding (1677) para 13

- ^ T Paine, Rights of Man (1792) 197

- ^ a b c d Pérez-Garzón, Carlos Andrés (xiv January 2018). "Unveiling the Meaning of Social Justice in Colombia". Mexican Law Review. x (2): 27–66. ISSN 2448-5306. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Rousseau (1774). Journal encyclopédique... [Ed. Pierre Rousseau] (in French). De fifty'Imprimerie du Periodical.

- ^ Fifty'Esprit des journaux, françois et étrangers (in French). Valade. 1784.

- ^ L'Episcopato ossia della Potesta di governar la chiesa. Dissertazione (in Italian). na. 1789.

- ^ JS Manufacturing plant, Utilitarianism (1863)

- ^ "Divini Redemptoris (March 19, 1937) | PIUS XI". w2.vatican.va . Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "The Press: Crackdown on Coughlin". Time. 27 Apr 1942. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

- ^ Moyn, Samuel (2014). "The Underground History of Constitutional Dignity". Yale Man Rights and Development Journal. 17 (ane). ISSN 1548-2596.

- ^ FA Hayek, Law, Legislation and Liberty (1973) vol Ii, ch 3

- ^ Hunter Lewis (14 October 2009). "Sustainability, The Complete Concept, Environment, Healthcare, and Economic system" (PDF). ChangeThis. Archived from the original (PDF) on four March 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ John Allen Jr. (28 July 2009). "Ecology – The first stirring of an 'evolutionary spring' in late Jesuit's official standing?". National Cosmic Reporter. Archived from the original on 24 Baronial 2012.

- ^ Sandro Magister (11 Jan 2010). "Benedict XVI to the Diplomats: Three Levers for Lifting Upward the World". chiesa, Rome. Archived from the original on four March 2016.

- ^ Sowell, Thomas (5 February 2002). The quest for cosmic justice (1st Touchstone ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN0684864630.

- ^ John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (2005 reissue), Chapter 1, "Justice as Fairness" – 1. The Role of Justice, pp. 3–4

- ^ John Rawls, Political Liberalism 15 (Columbia University Press 2003)

- ^ John Rawls, Political Liberalism 291–92 (Columbia University Printing 2003)

- ^ James, Nickel. "Human Rights". stanford.edu. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved x Feb 2015.

- ^ Pogge, Thomas Pogge. "World Poverty and Human Rights". thomaspogge.com. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- ^ Northward, James (23 September 2014). "The Resources Privilege". The Nation. Archived from the original on ten Feb 2015. Retrieved x Feb 2015.

- ^ Pogge, Thomas. "Human Rights and Just Revenue enhancement – Global Financial Transparency". Archived from the original on ten February 2015.

- ^ Alison Thousand. Jaggar1 by, ed. (2010). Thomas Pogge and His Critics (ane. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN978-0-7456-4258-1.

- ^ Kahn, Elizabeth (June–December 2012). "Global Economic Justice: A Structural Approach". Public Reason. iv (i–2): 48–67.

- ^ "Earth Day of Social Justice, 20 Feb". www.un.org . Retrieved 8 Nov 2019.

- ^ a b c d eastward "Social Justice in an Open up Globe: The Role of the United nations", The International Forum for Social Development, Department of Economical and Social Diplomacy, Partitioning for Social Policy and Development, ST/ESA/305" (PDF). New York: United Nations. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2017.

- ^ a b "OHCHR | Convention on the Rights of the Kid". www.ohchr.org . Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Amy (ane June 2010). "Immature Evangelicals: Expanding Their Mission". Fourth dimension. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved viii Oct 2020.

- ^ Stott, John (29 November 2012). The Cross of Christ. InterVarsity Press. p. 185. ISBN978-0-8308-6636-6.

- ^ S. R. Valentine, John Bennet & the Origins of Methodism and the Evangelical revival in England, Scarecrow Press, Lanham, 1997.

- ^ Carey, Brycchan. "John Wesley (1703–1791)." The British Abolitionists. Brycchan Carey, 11 July 2008. 5 October 2009. Brycchancarey.com Archived 29 January 2022 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Wesley John, "Thoughts Upon Slavery," John Wesley: Holiness of Heart and Life. Charles Yrigoyen, 1996. five Oct 2009. Gbgm-umc.org Archived 16 October 2022 at the Wayback Car

- ^ "Do Justice". First Complimentary Methodist Church building. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church – 2012 ¶164 V, umc.org Archived half dozen December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Book of Bailiwick of The United Methodist Church building – 2008 ¶ 162 G, umc.org Archived six December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Seven Key Themes of Catholic Social Teaching". Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Matthew 25:xl.

- ^ Option for the Poor, Major themes from Catholic Social Teaching Archived 16 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Office for Social Justice, Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

- ^ Popularised by John A. Ryan, although run into Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb, Industrial Democracy (1897)

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – Social justice". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ John L. Esposito (1998). Islam and Politics. Syracuse University Printing. p. 17.

- ^ John L. Esposito (1998). Islam and Politics. Syracuse University Printing. p. 205.

- ^ John L. Esposito (1998). Islam and Politics. Syracuse University Press. pp. 147–viii.

- ^ Sacks, Jonathan (2005). To Heal a Fractured Globe: The Ethics of Responsibility. New York: Schocken. p. 3. ISBN9780826486226.

- ^ Patil, Vijaykumar (26 Jan 2015). "Caste arrangement hindering the goal of social justice: Siddaramaiah". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015.

- ^ Lee Jen-der (2014), "Offense and Penalization: The Case of Liu Hui in the Wei Shu", Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook, New York: Columbia University Printing, pp. 156–165, ISBN 978-0-231-15987-half-dozen.

- ^ Simply Comment – Volume three Number i, 2000

- ^ Capeheart, Loretta; Milovanovic, Dragan. Social Justice: Theories, Issues, and Movements.

- ^ In the mass media, 'Liberation Theology' can sometimes be used loosely, to refer to a wide variety of activist Christian idea. This article uses the term in the narrow sense outlined here.

- ^ Berryman, Phillip, Liberation Theology: essential facts nigh the revolutionary movement in Latin America and beyond(1987)

- ^ "[David] Horowitz commencement describes liberation theology as 'a course of Marxised Christianity,' which has validity despite the awkward phrasing, but then he calls it a form of 'Marxist-Leninist ideology,' which is simply not truthful for nearly liberation theology..." Robert Shaffer, "Acceptable Bounds of Academic Discourse Archived four September 2013 at the Wayback Auto," Organisation of American Historians Newsletter 35, Nov 2007. URL retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ Liberation Theology and Its Role in Latin America. Elisabeth Erin Williams. Monitor: Journal of International Studies. The Higher of William and Mary.

- ^ Sarah Kleeb, "Envisioning Emancipation: Karl Marx, Gustavo Gutierrez, and the Struggle of Liberation Theology [ permanent dead link ] "; Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Society for the Study of Religion (CSSR), Toronto, 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2012. [ dead link ]

- ^ Richard P. McBrien, Catholicism (Harper Collins, 1994), chapter 4.

- ^ Gustavo Gutierrez, A Theology of Liberation, Starting time (Castilian) edition published in Lima, Peru, 1971; beginning English edition published by Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York), 1973.

- ^ Farmer, Paul E., Bruce Nizeye, Sara Stulac, and Salmaan Keshavjee. 2006. Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine. PLoS Medicine, 1686–1691

- ^ Cueto, Marcos. 2004. The ORIGINS of Primary Health Care and SELECTIVE Primary Wellness Care. Am J Public Health 94 (eleven):1868

- ^ Hofrichter, Richard (Editor) (2003). Health and social justice: Politics, ideology, and inequity in the distribution of disease. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. ISBN9780787967338.

- ^ Vienna Announcement and Program of Action, Part II, paragraph lxxx

- ^ EA Posner and CR Sunstein Global Warming and Social Justice

- ^ JS Mastaler Social Justice and Environmental Displacement

- ^ A Dahlberg, R Rohde, Grand Sandell (2010) National Parks and Environmental Justice: Comparing Access Rights and Ideological Legacies in Three Countries Archived 1 March 2022 at the Wayback Auto eight, no. 3 pp.209-224

- ^ RD Bullard (2005) The Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution (Counterpoint) ISBN 978-1578051205

- ^ a b c Novak, Michael. "Defining social justice." First things (2000): 11-12.

- ^ Hayek, F.A. (1982). Police, Legislation and Liberty, Vol. two. Routledge. p. 78.

- ^ O'Neill, Ben (sixteen March 2011) The Injustice of Social Justice Archived 28 Oct 2022 at the Wayback Car, Mises Institute

Further reading [edit]

Articles [edit]

- C Pérez-Garzón, 'What is social justice? A new history of its pregnant in the transnational legal discourse' (2019) 43 Revista Derecho del Estado 67-106, originally in Spanish: '¿Qué es justicia social? Una nueva historia de su significado en el discurso jurídico transnacional'

- LD Brandeis, 'The Living Law' (1915–1916) 10 Illinois Police Review 461

- A Etzioni, 'The Fair Order, Uniting America: Restoring the Vital Centre to American Democracy Archived 24 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine' in Northward Garfinkle and D Yankelovich (eds) (Yale University Printing 2005) pp. 211–223

- Otto von Gierke, The Social Office of Individual Law (2016) translated and introduced by E McGaughey, originally in High german Dice soziale Aufgabe des Privatrechts

- M Novak, 'Defining Social Justice' (2000) Showtime Things

- B O'Neill, 'The Injustice of Social Justice' (Mises Institute)

- R Pound, 'Social Justice and Legal Justice' (1912) 75 Central Police force Journal 455

- M Powers and R Faden, 'Inequalities in health, inequalities in health care: four generations of discussion about justice and cost-effectiveness analysis' (2000) ten(2) Kennedy Inst Ethics Periodical 109–127

- M Powers and R Faden, 'Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Wellness Care: An Ethical Analysis of When and How They Matter,' in Diff Handling: Confronting Racial and Indigenous Disparities in Health Care (National Academy of Sciences, Constitute of Medicine, 2002) 722–38

- United Nations, Department of Economical and Social Affairs, 'Social Justice in an Open Globe: The Part of the Un' (2006) ST/ESA/305

Books [edit]

- AB Atkinson, Social Justice and Public Policy (1982) previews

- Gad Barzilai, Communities and Police: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities (University of Michigan Press) analysis of justice for non-ruling communities

- TN Carver, Essays in Social Justice (1915) Chapter links.

- C Quigley The Evolution of Civilizations: An Introduction to Historical Analysis (1961) 2nd edition 1979

- P Corning, The Off-white Guild: The Science of Homo Nature and the Pursuit of Social Justice (Chicago UP 2011)

- WL Droel What is Social Justice (ACTA Publications 2011)

- R Faden and One thousand Powers, Social Justice: The Moral Foundations of Public Wellness and Health Policy (OUP 2006)

- J Franklin (ed), Life to the Full: Rights and Social Justice in Australia (Connor Court 2007)

- LC Frederking (2013) Reconstructing Social Justice (Routledge) ISBN 978-1138194021

- FA Hayek, Law, Legislation and Freedom (1973) vol II, ch three

- G Kitching, Seeking Social Justice through Globalization: Escaping a Nationalist Perspective (2003)

- JS Manufactory, Utilitarianism (1863)

- T Massaro, S.J. Living Justice: Catholic Social Teaching in Activeness (Rowman & Littlefield 2012)

- John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Harvard University Press 1971)

- John Rawls, Political Liberalism (Columbia University Press 1993)

- C Philomena, B Hoose and Thou Mannion (eds), Social Justice: Theological and Practical Explorations (2007)

- A Swift, Political Philosophy (3rd edn 2013) ch 1

- Michael J. Thompson, The Limits of Liberalism: A Republican Theory of Social Justice (International Journal of Ideals: vol. 7, no. 3 (2011)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_justice

0 Response to "Social Justice Shirts Make Science Great Again"

Post a Comment